Experiencing Movement and Rest in Music

What denotes movement and rest in music?

And what did Jesus mean by telling his disciples that “the sign of the Father in you” is “a movement and a rest?”

Movement is a familiar impulse, as rest is an equally familiar instinct. They are components of our bodily existence, occurring often involuntarily. Usually they manifest without any particular effort of attention, directed or divided. To understand the parable of Jesus, we have to examine the ideas of movement and rest in a different context.

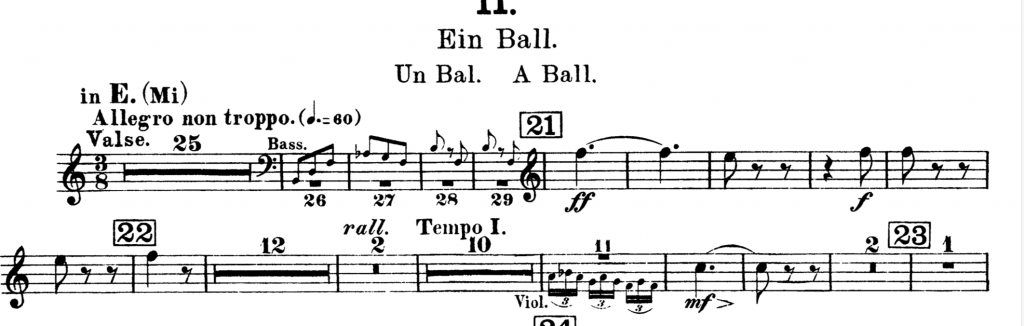

In music, movement, both for the performer and the listener, occurs when sounds are produced. Usually the sounds are linked in a melodic line, which draws the listener along with it. In most musical scores, many cues are given as to how the music should move, what its rhythms should be, its volume, its speed. The conductor transmits these cues to the performers who actualize them.

Resting within a Musical Performance

What happens when there is a rest? What is the composer’s intent, the conductor’s directive, and the performer’s obligation? In the language of the Fourth Way, what is the intent of higher centers, what is the steward’s directive, and the job of work I’s?

“As we must account for every idle word, so must we account for every idle silence.” – Benjamin Franklin

Most conductors will counsel their musicians to be active during the rests; indeed, most active at those times. What is this activity? Whether the rest endures for a single beat, a measure, or a longer section, it is the musician’s obligation to be actively attentive. He must focus on what is around him, the time and harmonies that are elapsing, the cues for his entry. As in this part to a symphony by Berlioz, where the horn player rests for 59 measures and plays for 9:

Naturally, we hope for a similar quality of attention while the musician is playing. Yet while playing, his foremost role is in producing sounds, directing his attention to the mechanisms which enable him to do so. Because the moving center is a strong focus of a musician’s identity, one can feel more “awake” when it is active.

Awareness of Movement and Rest in Music

Many spiritual traditions recognize the value of movement in bringing awareness and attention to the moment, through ritual prayer, singing, or dances. When we fully engage, we experience a degree of focus and alertness.

However, this attention is temporary, not usually under our volition. In such a case, as T.S. Eliot said, “You are the music while the music lasts.” The same can be said of movement.

In music, during the rests, there is more opportunity for divided attention, a higher awareness.

When one center (even if it is the intellectual part of the center) occupies all of our attention, awareness can be veiled by the illusion of mastery and control. When a rest occurs, particularly a rest of significant duration, it serves as a kind of fixative. Rest is a reminder of the state that is possible when one interrupts identification and divides attention. In this sense, it serves the same function as Gurdjieff’s stop exercise. Afterwards, one can resume the active process of listening or playing an instrument with greater relativity, or a more detailed hearing.

The Music of Silence

Eventually, over time, music creates pathways and resonates without sound in the heart.

“The music in my heart I bore, long after it was heard no more.” – William Wordsworth

The highest level of listening is a function of higher centers. When it happens, one can experience harmony as a “music of the spheres,” inaudible to bodily ears. It is a music that resonates through silence.